The Machine That Could Build

My father’s office smelled like old paper and machine oil. I was seven, trailing behind him through corridors of identical desks, until we reached it: an IBM computer, beige and humming, its green cursor blinking on a black screen.

“Watch this,” Dad said, and typed something I couldn’t read. The screen exploded into motion. Tiny paratroopers fell from a pixelated sky while I frantically mashed keys, trying to shoot them down before they landed.

I’d seen televisions. I’d used our VCR. But this was different. This machine responded. It waited for me. It changed based on what I did.

On the walk home, I didn’t say a word. I was trying to hold onto the feeling, like discovering that walls in your house were actually doors, and you’d been living in one room your entire life.

The Resistance

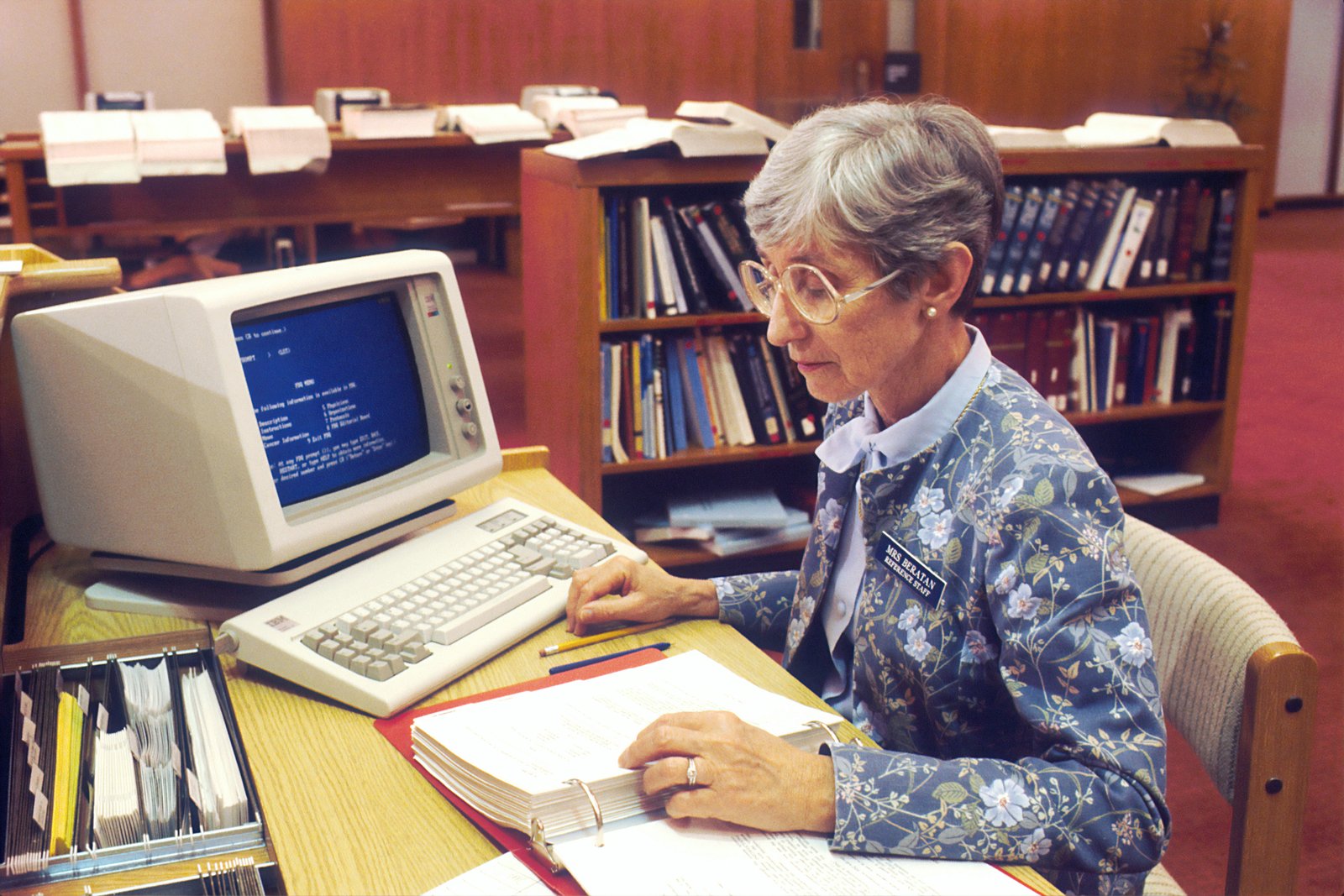

It was 1993 in our small Eastern Indian town, and the bank where my father worked was facing change. Employees were uneasy. The unions were vocal. Their concern? Computers were coming, and no one knew what that meant for their jobs.

The ledger clerks saw their future in those beige boxes, and it looked uncertain. Management offered programming courses in FORTRAN and BASIC to anyone interested. “Reskilling,” they called it. My father, a math major who loved calculus the way some people love cricket, signed up immediately.

He’d come home with thick manuals, muttering about loops and variables while my mother rolled her eyes. Then my sister was born, and the manuals gathered dust. But he never stopped talking about those machines. Never stopped believing they were the future, even when his colleagues remained sceptical.

Years later, I’d understand what he was trying to tell me: Every revolution looks like a threat until you’re holding the tools.

The Cassette Incident

I was eight when I discovered our cassette player could record. I spent an entire afternoon creating what I thought was a masterpiece: my own songs, my own radio show, complete with sound effects I made with my mouth.

I was so proud. Right up until my mother tried to play her favourite album and heard my warbling voice instead.

The cassette player was confiscated. I was grounded for a week. But I wasn’t sorry. I’d felt something while making those recordings: the same thing I felt playing Paratrooper in Dad’s office. The thrill of making something that existed only because I’d made it.

My cousin Ashu felt it too. We were the same age, best friends, and our fathers worked at the same bank. When we met, we didn’t talk about cricket or movies. We talked about the magical machines our dads had shown us. We made a pact: someday, we’d be geeks. We’d build things.

Looking back, I think we were responding to something in the air. India was changing. The software boom was beginning. We were too young to understand it, but we could feel it: the way animals sense earthquakes before they hit.

The Revolution (30 Minutes at a Time)

In 4th grade, my school added computer class. One 30-minute theory session. One 30-minute practical. Once a week. No exams, no grades—just an experiment.

Most kids treated it like recess. But for those of us who’d been waiting, it was church.

We learned DOS commands first. I still remember the rush of typing DIR and watching the screen fill with file names, like I’d asked the computer a question and it had answered. Then came Windows 95, and the mouse: suddenly you didn’t need a manual. The machine had learned to speak human.

By 8th grade, we were writing simple programs in C. I’d save my pocket money for the cybercafé down the street, where I’d spend hours playing Counter-Strike, sure, but also experimenting with code when no one was looking.

We still couldn’t afford a computer at home. “For what?” my mother would ask. “To play games?” She wasn’t wrong. Most middle-class families saw computers as expensive toys, not tools. The future hadn’t proven itself yet.

So I waited for Wednesdays. I waited for that 30-minute window when I could sit in front of a screen and feel like I was learning a language that would let me talk to machines.

The $700 Gateway

December 2001. My father brought home an HP computer in three large boxes. 256 MB of RAM. Windows XP. Cost him $700: more than he made in a month.

I didn’t sleep that night.

For the next three years, I barely slept at all. Counter-Strike. Prince of Persia. Grand Theft Auto.

When we got dial-up internet (64 kbps, the sound of robots screaming every time you connected), I discovered Orkut, AOL Messenger, and MySpace. I made friends in other countries. I joined forums. I lived online.

Every month, I convinced my dad to buy Digit magazine, four times the price of Reader’s Digest, but worth it for the free DVDs packed with game demos, software trials, and utilities. Ashu and I would meet and trade our discs, discussing every piece of software like scholars analysing ancient texts.

But here’s what I didn’t notice: I’d stopped creating.

That child who’d overwritten his mother’s cassettes? Who’d begged his father for office visits just to type DOS commands? He was gone. I’d become a consumer. An addict, really, chasing the next game, the next forum thread, the next notification.

Programming was something I’d learned in school, past tense. The builder in me was dormant, buried under gigabytes of pirated games and forum posts.

The Senior on the Lawn

First year of college, Computer Science major. I was doing well in C programming, loved the logic, the mathematical elegance of functional code. But I was frustrated. My programs lived and died on my machine. No one else could use them. And storing data meant writing to clunky text files that would corrupt if you looked at them wrong.

One afternoon, lying on the campus lawn between classes, I started complaining about this to a senior I’d just met. He was different from most students, already running a software agency while in school, building websites for American clients.

He listened to my rant about C programs and flat files, then smiled. “Come to the city this weekend. There’s a bootcamp. Two days. Bring your laptop.”

“What are they teaching?”

“How to build things people can actually use.”

The Weekend That Changed Everything

Day 1: HTML and CSS. By evening, I’d built a webpage and hosted it on free shared hosting. My work was live. Anyone with internet could see it. I called my father. “Dad, I built something. It’s on the internet. You can see it.”

The wonder in his voice matched what I was feeling.

Day 2: PHP and the LAMPP stack. Suddenly, every problem I’d had (distribution, data storage, user interfaces) had solutions. PHP felt like C’s extroverted cousin, chatty and social, designed for the web.

I bought an 800-page PHP manual that night. For the next three months, that book and my laptop were surgically attached to me. I pulled all-nighters writing code, driven by the electric feeling of building something real.

My first real project: an attendance tracker. Students could log their classes, see how many lectures they’d missed, leave notes for classmates. It solved a genuine problem, too many people were paying penalties because they didn’t realize they’d missed the minimum attendance requirement.

The app spread. People started calling me “the hacker guy.” I wasn’t hacking anything, but the name stuck. So did something else: the feeling I’d lost at eight years old, when my cassette player was taken away.

I was building again.

Jobs

I became obsessed with Steve Jobs. Read everything about him. Watched Pirates of Silicon Valley three times. Talked about him so much that people started calling me “Jobs” around campus.

I joined Opera’s Campus Crew, installing Opera Mini on every Nokia phone I could find, wearing their t-shirts like a uniform. For my final year dissertation, I spent twelve months building a motorcycle review site from scratch: authentication system, CMS, autocomplete search, commenting engine. Every line of code written by hand.

Looking back, I was trying to channel something. That relentless focus Jobs had. That belief that you could will beautiful things into existence through sheer obsessive attention to detail.

“Stay hungry, stay foolish,” he’d said. I was both, rabidly.

The Spark That Caught

Today, I’m a Frontend Engineer. I’ve worked for startups across continents. I’ve built products used by thousands of people. None of it would have happened without that senior on the college lawn who said, “Try this weekend bootcamp.”

But here’s what I think about now: What if my father hadn’t taken me to his office that day in 1993? What if my school hadn’t offered those experimental Wednesday computer classes? What if I hadn’t met that senior, on that specific afternoon, when I was frustrated enough to listen?

We love to talk about hard work and talent. But what about luck? What about timing? What about the strangers who redirect your life with a single sentence and never know it?

My father stood against his colleagues when they protested computers. He saw something they didn’t, or couldn’t. He brought those machines home, into my life, at a cost he could barely afford. That wasn’t luck. That was love.

And maybe that’s the real story. Not a kid who learned to code. But a father who believed in a future he’d never see, and did everything he could to give his son a chance to live in it.

The cursor blinks. The screen waits. The machine, still, after all these years, responds. What will you build?